R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Company

| |

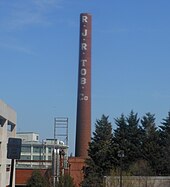

The RJR Plaza Building in Winston-Salem, headquarters of RJR since 2008 | |

| Company type | Subsidiary |

|---|---|

| Industry | Tobacco |

| Founded | 1875[1] |

| Founder | Richard Joshua Reynolds |

| Headquarters | |

Key people | James Murphy (Chairman) Bernd Meyer (President) Jorge Araya (CEO and CCO) |

| Products | Cigarettes |

Number of employees | 4,000[2] |

| Parent | Reynolds American |

| Website | rjrt.com |

The R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Company (RJR) is an American tobacco manufacturing company based in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. Founded by namesake R. J. Reynolds in 1875,[1] it is the largest tobacco company in the United States. The company is a wholly owned subsidiary of Reynolds American, itself a wholly owned subsidiary of British American Tobacco.

RJR has a large brand portfolio, which includes Camel, Newport, Doral, Eclipse, Kent, and Pall Mall. Other brands commercialized in the past included Barclay, Belair, and Real.

History

[edit]Early history

[edit]

The son of a tobacco farmer in Virginia, Richard Joshua "R. J." Reynolds sold his shares of his father's company in Patrick County, Virginia, and ventured to the nearest town with a railroad connection, Winston-Salem, to start his own tobacco company.[3] He bought his first factory building from the Moravian Church and established the "little red factory" with seasonal workers. The first year, he produced 150,000 pounds (68,000 kg) of tobacco; by the 1890s, production had increased to several million pounds per year.[3] The company's factory buildings were the largest buildings in Winston-Salem, with new technologies such as steam power and electric lights.[3] The second primary factory building was the oldest Reynolds factory still standing and was sold to Forsyth County in 1990.[3]

At the beginning of the 1900s, Reynolds bought most of the competing tobacco factories in Winston-Salem.[3] The company produced 25% of America's chewing tobacco.[3] 1907's Prince Albert smoking tobacco became the company's national showcase product, which led to high-profile advertising in New York City's Union Square.[3] The Camel cigarette became the most popular cigarette in the country. The Reynolds company imported so much French cigarette paper and Turkish tobacco for Camel cigarettes that Winston-Salem was designated by the United States federal government as an official port of entry for the United States, despite the city being 200 miles (320 km) inland.[3] Winston-Salem was the eighth-largest port of entry in the United States by 1916.[3]

In 1917, the company bought 84 acres (34 ha) of property in Winston-Salem and built 180 houses that it sold at cost to workers, to form a development called "Reynoldstown".[3]

At the time Reynolds died in 1918 (of pancreatic cancer), his company owned 121 buildings in Winston-Salem.[3] He was so integral to company operations that executives did not hang another chief executive's portrait next to Reynolds's in the company board room until 41 years later.[3] Reynolds's brother William Neal Reynolds took over following Reynolds's death, and six years later Bowman Gray became the chief executive. By that time, Reynolds Co. was the top taxpayer in the state of North Carolina, paying $1 out of every $2.50 paid in income taxes in the state, and was one of the most profitable corporations in the world.[3] It made two-thirds of the cigarettes in the state.[3]

Reynolds Co.'s success during this period can also be measured by the concurrent success of many Winston-Salem companies that received large amounts of business from Reynolds: Wachovia National Bank became one of the largest banks in the Southeast, and the company's law firm Womble Carlyle Sandridge & Rice became the largest law firm in North Carolina.[4]

R. J. Reynolds Tobacco diversified into other areas, buying Pacific Hawaiian Products, the makers of Hawaiian Punch, in 1962, Sea-Land Service in 1969, and Del Monte Foods in 1979. Sea-Land was spun off in 1984.[5]

Because of the company's diversification, the company changed its name to R. J. Reynolds Industries, Inc. in 1970. R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Co. was a subsidiary.[6]

RJR Nabisco

[edit]R. J. Reynolds Industries merged with Nabisco Brands in 1985, and the name changed to RJR Nabisco in August 1986.[6] In 1987, a bidding war ensued between several financial firms to acquire RJR Nabisco. Finally, the private equity takeover firm Kohlberg Kravis and Roberts & Co (commonly referred to as KKR) was responsible for the 1988 leveraged buyout of RJR Nabisco. This was documented in several articles in The Wall Street Journal by Bryan Burrough and John Helyar. These articles were later used as the basis of a bestselling book, Barbarians at the Gate: The Fall of RJR Nabisco,[7] and then into a television movie. As a result, in February 1989, RJR Nabisco paid executive F. Ross Johnson US$53,800,000 as part of a golden handshake clause, the largest such deal in history at the time,[8] as severance compensation for his acceptance of the KKR takeover. He used the money to open his own investment firm, RJM Group, Inc.[9] In 1999 RJR Nabisco spun off R. J. Reynolds Tobacco, which began trading on June 15 as R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Holdings, Inc., and a year later announced it would buy Nabisco Group Holdings Inc., the company that had been RJR Nabisco. This followed the sale of Nabisco Holdings Group to Philip Morris.[6]

Recent history

[edit]In 1994, then CEO James Johnston testified under oath before Congress, saying that he didn't believe that nicotine is addictive.[10] In 1998, the company was part of the Tobacco Master Settlement Agreement with 46 U.S. states, agreeing to pay smoking-related health care costs and restrict advertising in return for protection against private lawsuits.

In 1999, R. J. Reynolds was spun out of RJR Nabisco. The same year, the company sold all its non-U.S. operations to Japan Tobacco, which made those operations into its international arm, JT International. Consequently, any Camels, Winstons or Salems sold outside the United States are now actually Japanese cigarettes.

In 2002, the company was fined $15 million for handing out free cigarettes at events attended by children, and was fined $20 million for breaking the 1998 Master Agreement, which restricted targeting youth in its tobacco advertisements.[11]

In 2001–2011, the European Union was involved in three civil suits against R. J. Reynolds in the United States District Court for the Eastern District of New York, accusing the company of selling black market cigarettes to drug traffickers and mobsters from Italy, Russia, Colombia and the Balkans. The suits were unsuccessful.[12][13][14][15]

On July 30, 2004, R. J. Reynolds merged with the U.S. operations of British American Tobacco (operating under the name of Brown & Williamson). A new parent holding company, Reynolds American Inc., was established as part of the transaction.

In May 2006 former R. J. Reynolds vice-president of sales Stan Smith pleaded guilty to charges of defrauding the Government of Canada of $1.2 billion (CDN) through a cigarette smuggling operation. Smith confessed to overseeing the 1990s operation while employed by RJR. Canadian-brand cigarettes were smuggled out of and back into Canada, or smuggled from Puerto Rico, and sold on the black market to avoid taxes. The judge referred to it as biggest fraud case in Canadian history.[16]

Since 2006, R. J. Reynolds has been the subject of a Farm Labor Organizing Committee (FLOC) campaign to reduce the exploitative nature of its tobacco procurement system. FLOC's goal is to meet with Reynolds executives, growers, and workers in collective bargaining to improve farmworkers' pay and living conditions. Although there are many layers of subcontractors within the procurement system that seemingly absolve Reynolds of responsibility, FLOC asserts that its executives have the ability to make changes within the system due to their wealth and enormous power. Despite repeated refusals to meet from CEO Susan Ivey, FLOC continues the campaign against R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Company.[17]

In 2010, Reynolds American announced that the company would close its manufacturing plants in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, and Puerto Rico. Production from these plants will be moved to the Tobaccoville, North Carolina, plant.[18]

On July 15, 2014, Reynolds American agreed to buy Lorillard Tobacco Company for $27.4 billion.[19] The deal also included the sale of the Kool, Winston, Salem, and blu brands to Imperial Tobacco for $7.1 billion.[20]

In January 2017, Reynolds American agreed to a $49.4 billion deal to be taken over by British American Tobacco.[21] The deal was completed July 25, 2017.[22]

Marketing, sponsorships and criticisms

[edit]From 1972, R. J. Reynolds was a title sponsor of the NHRA Winston Drag Racing Series, the NASCAR Winston Cup Series and until 1993, the IMSA Camel GT for sportscars.

The NHRA sponsorship lasted up to 2001, before a new governing rule called the Master Settlement Agreement, which restricted R. J. Reynolds to one sponsorship of a sporting event; the company sponsored NASCAR up to 2003.

The Lotus Formula One team was sponsored by Camel from 1987 until 1990.

RJR brand Winston was a sponsor of the 1982 FIFA World Cup whilst fellow RJR brand Camel was a sponsor of the 1986 FIFA World Cup.[23]

In late 2005, R. J. Reynolds opened the Marshall McGearty Lounge in the Wicker Park neighborhood of Chicago as part of a marketing strategy to promote a brand of "superpremium" cigarettes and counteract local smoking bans in restaurants and cafes that took effect in 2006. The lounge, which offered thirteen varieties of exclusive "hand-crafted" cigarette, along with alcohol and "light food", had been "well received" in the neighborhood and by the targeted upscale market, according to company officials. The lounge has since been closed due to Illinois indoor smoking restrictions. The company planned to open a second location in Winston-Salem in the summer of 2007, but abandoned those plans within weeks of opening, citing the increasing number of smoking restrictions in public places by state and local governments.[24]

Joe Camel

[edit]In 1987, RJR resurrected the mascot for their Camel brand of cigarette, Joe Camel. Joe Camel, an anthropomorphic cartoon camel wearing sunglasses, was claimed to be a ploy to entice and interest the underaged in smoking. R. J. Reynolds maintained that Joe's "smooth character" was meant only to appeal to adult smokers.

This criticism was reinforced by a 1991 study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association[25] showing that more children five and six years old could recognize Joe Camel than could recognize Mickey Mouse or Fred Flintstone (coincidentally, Fred Flintstone was also once used to sell R. J. Reynolds's Winston cigarettes) and alleged that the Joe Camel advertisement campaign was targeting children, despite R. J. Reynolds's contention that the campaign had been researched only among adults and was directed only at the smokers of other brands. In response to this criticism, RJR instituted "Let's Clear the Air on Smoking", a campaign of full-page advertisements consisting entirely of large type text, which denied the charges and declared that smoking is "an adult custom".

Early knowledge of the harms of cigarettes

[edit]By 1953, R. J. Reynolds held an internal belief that cigarettes caused cancer.[26] On February 2 of that year, R. J. Reynolds research chemist and executive Claude Teague released 'Survey of Cancer Research', a confidential internal document for R. J. Reynolds upper management.[27] He concluded that clinical data was confirming the fact that tobacco was "an important etiologic factor in the induction of primary cancer of the lung". He also wrote that many findings of animal studies "would seem to indicate the presence of carcinogens".[28]

Lawsuits

[edit]In May 2011, a Miami-Dade Circuit jury awarded Julie Reese, an 82-year-old Cape Coral smoker represented by The Ferraro Law Firm, a total verdict of $1 million from R. J. Reynolds Tobacco, after she developed laryngeal cancer and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The jury found Reynolds to be negligent, guilty of fraud by concealment and fraud conspiracy, and guilty of placing a defective product on the market.[29][30]

On February 25, 2020, Chief Judge Rodney Gilstrap of the United States District for the Eastern District of Texas determined that Reynolds remained liable for its full portion of an annual $8 billion settlement payment based on a settlement agreement that Reynolds reached with the State of Texas in 1998.[31] Reynolds had previously claimed that its divestiture of several brands to Imperial Tobacco Group Brands, LLC had extinguished its obligation to make payments for those brands under the 1998 Settlement Agreement. Chief Judge Gilstrap disagreed in a 92-page memorandum opinion and order, finding that Reynolds's position was "oppressive, inequitable, and unreasonable" in addition to being contrary to governing law.[32]

Brands

[edit]R. J. Reynolds brands include Newport, Camel, Doral, Eclipse, Kent and Pall Mall. Brands still manufactured but no longer receiving significant marketing support include Capri, Carlton, GPC, Lucky Strike, Misty, Monarch, More, Now, Old Gold, Tareyton, Vantage, and Viceroy. Discontinued brands include Barclay, Belair, and Real. The company also manufactures certain private-label brands. Five of the company's brands are among the top ten best selling cigarette brands in the United States, and it is estimated that one in three cigarettes sold in the country were manufactured by R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Company. In 2010 R. J. Reynolds acquired the rights to the smokeless tobacco products Kodiak and Grizzly dip.

Uptown

[edit]In 1990, R. J. Reynolds planned to launch a new cigarette brand called Uptown, aimed primarily at African-Americans. To appeal to black Americans seeking a less pronounced menthol taste (similar to Lorillard's Newport, which was gaining share), Reynolds decided against using green on the packaging, and instead used black and gold, the colors of luxury European cigarettes.[33]

Narrowing the marketing further, Uptown cigarettes were to be packed with filters facing down, the reverse of the usual arrangement. Market research indicated that many African-American smokers open packs from the bottom, possibly to avoid crushing the filters.[33] It was later discovered that cigarette packs were opened from the bottom for a different reason: "This phenomenon traces back at least to World War II, when cigarettes were a valued commodity among soldiers. Often a soldier temporarily without cigarettes and without funds would bum a smoke from a fellow soldier. It was impolite to refuse such a request. However, there were two occasions when a refusal was not considered impolite: if there was only one cigarette left in the pack and if the pack was not yet opened. A pack opened from the bottom and resting, as it normally did, in a shirt pocket would appear unopened. Therefore, the soldier in possession of cigarettes would be able to avoid having to give too many away."[34]

The promotional blitz was scheduled to begin on February 5, 1990, and Philadelphia was selected as the test market because of its large black population. Before it began, the campaign came under fire from religious, health and black-interest groups who expressed concerns about promoting cigarette smoking to African-Americans.[35]

On January 19, 1990, Reynolds abruptly decided to cancel the cigarette, saying that the test marketing would no longer be reliable because of what it called, "the unfair and biased attention that brand has received".[35]

Facilities

[edit]Downtown

[edit]R. J. Reynolds built the "Little Red Factory" in 1892. It was uncertain whether it was torn down or made a part of Building 256-1, one of several red brick buildings on Chestnut Street built between 1911 and 1925. Much of the Building 256 complex burned in one of the city's worst fires ever on August 27, 1998, when the former factories were being renovated for Piedmont Triad Research Park. Albert Hall, or Building 256-9, was made of concrete and did not burn but had smoke damage; it was used for training until 1990 and was being renovated in 1998.[36]

In 1916, the first of five buildings known as Plant 64 between Fourth and Fifth Streets was built.[37] The 400,000-square-foot Plant 64 was the oldest remaining Reynolds plant when it was renovated at a cost of $55 million into 242 apartments, with the first residents moving in on July 1, 2014.[38][39]

The last building used for making cigarettes downtown was Building No. 12 across Second Street from the Building 256 complex, which Forsyth County bought when manufacturing ended there in 1990;[36] finished in 1916,[40] it was to be renovated for county offices after an announcement in 1999.[41] Building 60 was built in 1923 and later renovated.[42] Three buildings which were part of the "90 series" on Vine Street were later renovated;[43] the one at 525 Vine was built in 1926,[44] while Buildings 90-3 and 90-1A at 635 Vine, used for tobacco processing, were built in the early 1960s.[45][46] Building 91, a machine shop built in 1937, was later renovated and became part of the research park.[47] Bailey Power Plant, a coal-fired plant built in 1947, included Buildings 23-1, 23-2 and the Morris Building, and was used until 1997 and later became part of the research park.[48][49][50]

The company's headquarters were located in the Reynolds Building in Winston-Salem for more than 50 years. Built in 1929, the 21-story building was designed by the same architects (Shreve & Lamb) who later designed the Empire State Building in New York City.[51][52]

Reynolds Boulevard

[edit]The first R. J. Reynolds buildings on present-day Reynolds Boulevard (formerly 33rd Street[53]) were the three-story leaf buildings, the 2-1 building built in 1937 and the 2-2 building in 1955. These were named to the National Register of Historic Places in October 2017, and in October 2019 C.A. Harrison Cos. LLC, developer of Plant 64, announced the buildings would be renovated for loft apartments.[54]

Built in 1961 at a cost of $32 million ($271 million in 2023 dollars),[55] the Whitaker Park plant had 790,300 square feet of manufacturing space and was considered "the world's largest and most modern cigarette-manufacturing plant".[56] It was announced in May 2010 that cigarette manufacturing would cease at Whitaker Park; by mid-2011, this had been done. Manufacturing formerly performed at the Whitaker Park plant was consolidated in the more-modern Tobaccoville plant. On January 7, 2015, Reynolds announced that Whitaker Park was being donated to Whitaker Park Development Authority Inc., started in April 2011 by Winston-Salem Business Inc., the Winston-Salem Alliance and Wake Forest University.[56] In 2019 Cook Medical announced it would buy the 850,000-square-foot 601-1 building with plans to move its 650 employees there by 2022. As of October 2019, Hanesbrands had taken over space in the 426,800-square-foot 601-11 building as a distribution center, and Nature's Value bought that building in August 2021.[54][57]

On August 23, 2023, Cook Medical, which paid $4 million for its space in Whitaker Park in 2021, announced it would sell because the remote work trend meant it no longer needed the space. Purple Crow chief executive and president Dan Calhoun confirmed his company had a contract to buy the property. Purple Crow, which had already asked for incentives from the city, pledged in its incentive request to spend $50 million and create 274 jobs, nearly doubling its area work force.[55]

18 buildings and 100 acres in the area continue to be used for tobacco processing and warehousing.[55]

Headquarters buildings

[edit]In September 1977, R. J. Reynolds Industries moved the first of 1200 headquarters employees into the not-yet-completed,[58] $40 million,[59][60] 519,000-square-foot[61] glass and steel World Headquarters Building[59][60] being built across Reynolds Boulevard from the Whitaker Park plant.[62] At the same time, the company had plans for a new skyscraper downtown.[58]

The current headquarters, the RJR Plaza Building, is 16 stories tall and was completed in 1982 adjacent to the original 1929 Reynolds Building.[63] The tobacco company moved its headquarters to RJR Plaza in 1982, and the 1929 building continued to be used for some company offices until 2009;[64] the older building stood vacant[65] until new owners in 2014 began the process to convert it to a hotel.[66]

With the parent company (renamed RJR Nabisco in 1985 after merging with Nabisco) planning to move its headquarters to Atlanta in September 1987, the company donated the World Headquarters Building to Wake Forest University in January 1987, and in July of that year, the company voted to move its Planters-Life Savers division to one-third of that building.[59][60] In May 1999, BB&T bought what was then called the First Union Building for $2.5 million from Aon Consulting Inc., which moved about 400 employees to the former headquarters building which was called University Corporate Center.[67] In 2010, the building's tenants were Aon, BB&T, and PepsiCo.[62] On November 1 of that year, Pepsi announced 195 new jobs and a $7.5 million expansion of University Corporate Center, with BB&T moving two of its operations to Reynolds Business Center.[68] Aon and Pepsi remained the primary occupants in 2015.[69]

Other facilities

[edit]The Ziglar Sheds, Buildings 82 and 83 on East 25th Street in Winston-Salem, were built in the 1920s, the first warehouses built for tobacco storage according to company specifications, and sold in 1992. In 2024 they were being considered for the National Register of Historic Places.[70]

R. J. Reynolds's largest plant, Tobaccoville, a 2-million-square-foot (190,000 m2) facility constructed in 1986, is located in the town of Tobaccoville, North Carolina near Winston-Salem.

Macon manufacturing, located in Macon, Georgia, resides in a 1.4-million-square-foot (130,000 m2) facility built in 1974. This manufacturing plant was formerly known as Brown & Williamson, which was purchased by Reynolds and eventually closed in 2006.

R. J. Reynolds has a tobacco-sheet manufacturing operation in Winston-Salem. The sheet manufacturing operation in Chester, Virginia, was closed in 2006. Also, there are leaf operations in Wilson, North Carolina; tobacco-storage facilities in Blacksburg, South Carolina, and Richmond, Virginia; and a significant research-and-development facility in Winston-Salem.

A manufacturing plant in Puerto Rico was closed in 2010. Among these facilities, R. J. Reynolds employs approximately 6,800 people.

R. J. Reynolds's subsidiary, "R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Foreign Sales Corporation", is established in the British Virgin Islands to minimize its tax liability.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Frank Tursi, Susan E. White and Steve McQuilkin (1999). "In the Belly of the Beast". Winston-Salem Journal. Archived from the original on 2010-07-12.

- ^ "Who We Are". rjrt.com. Reynolds American. 2010. Archived from the original on 24 April 2015. Retrieved 30 May 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Tursi, Frank (1994). Winston-Salem: A History. John F. Blair, publisher. pp. 110–11, 184, 196–197. ISBN 9780895871152.

- ^ Burrough, Bryan (2003). Barbarians at the Gate. HarperCollins. p. 40. ISBN 9780060536350.

- ^ Debbie Norton (February 22, 1984). "Reynolds to spin off Sea-Land". Star-News.

- ^ a b c "A Stock History – Sequence of Events" (PDF). Retrieved 2012-03-23.

- ^ Burrough, Bryan; John Helyar (2003). Barbarians at the Gate: The Fall of RJR Nabisco. New York: HarperCollins. p. 592. ISBN 0-06-165554-6. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

barbarians at the gate.

- ^ "The high cost of parting ways with CEOs". CBC News. 9 June 2009. Archived from the original on November 12, 2010. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- ^ Mike Billips (24 July 1998). "Sons mind moguls' money". Atlanta Business Chronicle. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- ^ Hilts, Philip J. (April 15, 1994). "Tobacco Chiefs Say Cigarettes Aren't Addictive". The New York Times.

- ^ "BBC: Tobacco companies tell kids: 'Don't smoke!'". Retrieved 2008-06-14.

- ^ Helena Keers, "RJ Reynolds faces third EU suit" (November 1, 2002). Telegraph.

- ^ "R.J. Reynolds wins dismissal of European Community's RICO claims" (March 2011). Jones Day.

- ^ Henry Weinstein and Myron Levin, "R.J. Reynolds Accused Of Black Market Deals Archived 2013-07-23 at the Wayback Machine" (October 31, 2002). Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Tracey A. Basler, "Cigarettes, Smuggling, and Terror: The European Community v. RJ Reynolds" (2004). 4 JICL 3.

- ^ "Senior exec won't go to jail in massive fraud case", CBC News, May 4, 2006

- ^ Collins, Kristin. "Farm union targets RJR." News & Observer. October 27, 2007.

- ^ Craver, Richard (May 29, 2010). "RJR closing plant". Winston-Salem Journal. Retrieved 12 September 2018.

- ^ Bray, Michael J. de la Merced and Chad (15 July 2014). "To Compete With Altria, Reynolds American Is Buying Lorillard". Retrieved 23 October 2016.

- ^ Mangan, Dan (July 15, 2014). "Feeling blu? E-cig company spun off in major tobacco deal". CNBC.

- ^ "British American Tobacco Agrees to Pay $49 Billion to Take Full Control of Reynolds American". The Wall Street Journal. January 17, 2017. Retrieved January 17, 2017.

- ^ Craver, Richard (July 25, 2017). "Reynolds American now entirely owned by British American Tobacco". Winston-Salem Journal. Retrieved July 25, 2017.

- ^ "The Official FIFA World Cup Partners & Sponsors since 1982" (PDF). FIFA. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 7, 2012. Retrieved 12 September 2018.

- ^ "RJR drops plan for downtown smoking lounge", Winston-Salem Journal, June 9, 2007

- ^ Fischer PM, Schwartz MP, Richards JW Jr, Goldstein AO, Rojas TH. Brand logo recognition by children aged three to six years. Mickey Mouse and Old Joe the Camel. JAMA. 1991 Dec 11;266(22):3145-8. PMID 1956101

- ^ Cummings, K. Michael; Brown, Anthony; O'Connor, Richard (2007-06-04). "The Cigarette Controversy". Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 16 (6): 1070–1076. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0912. ISSN 1055-9965.

- ^ Proctor, Robert N (2012-02-16). "The history of the discovery of the cigarette–lung cancer link: evidentiary traditions, corporate denial, global toll: Table 1". Tobacco Control. 21 (2): 87–91. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050338. ISSN 0964-4563. PMID 22345227.

- ^ "Industry Documents Library". www.industrydocuments.ucsf.edu. Retrieved 2019-06-02.

- ^ "Smoker wins nearly $1 million award from R. J. Reynolds". The Ferraro Law Firm. May 23, 2011. Retrieved 2011-05-28.

- ^ Network, Courtroom View (20 May 2011). "Reynolds Liable for Damages in Smoker Case". Retrieved 23 October 2016.

- ^ "RJR Owes for Former Brands Under Landmark 1998 Tobacco Deal".

- ^ "RJ Reynolds Must Keep Paying Texas for '98 Settlement - Law360".

- ^ a b Ramirez, Anthony (1990-01-12). "A Cigarette Campaign Under Fire". The New York Times.

- ^ "Mystery of the Bottom-Opened Cigarette Pack". The New York Times. 1990-01-31.

- ^ a b "Industry Documents Library" (PDF). Retrieved 23 October 2016.

- ^ a b Scheve, Kristin (1998-09-28). "No. 256 Complex Had Long History: Many Workers and Many Tobacco Products Passed Through the Old Buildings". Winston-Salem Journal. p. A12.

- ^ Daniel, Fran (2013-08-22). "Plant 64 project gets OK from historic commission". Winston-Salem Journal. Retrieved 2019-06-05.

- ^ Schneider, Keith (2015-04-28). "Technology Overtakes Tobacco in Winston-Salem, N.C." The New York Times. Retrieved 2019-06-06.

- ^ "Plant 64 Welcomes Residents". Wake Forest Innovation Quarter. 2014-06-09. Retrieved 2019-10-30.

- ^ "Forsyth County Government Center". Emporis. Archived from the original on June 6, 2019. Retrieved 2019-06-06.

- ^ Holmes, William L. (1999-02-19). "County Plans to Redo Factory As New Home; Board Would Use Old No. 12 Tobacco Building As a Headquarters for Its Administrative Units". Winston-Salem Journal. p. B1.

- ^ "Reynolds American Building 60". Emporis. Archived from the original on June 6, 2019. Retrieved 2019-06-06.

- ^ Craver, Richard (2013-09-18). "525@Vine space under renovation near research parks". Winston-Salem Journal. Retrieved 2019-06-06.

- ^ Daniel, Fran (2014-06-13). "525@vine officially opens in downtown research park". Winston-Salem Journal. Retrieved 2019-06-06.

- ^ Craver, Richard (2012-07-31). "Inmar to move support center into renovated Reynolds Tobacco buildings". Winston-Salem Journal. Retrieved 2019-06-06.

- ^ Covington, Owen (2014-03-31). "Inmar trumpets its arrival in Wake Forest Innovation Quarter as 900 workers march into new HQ". Triad Business Journal. Retrieved 2019-06-06.

- ^ Kelly, Susan Stafford (2015-02-12). "Inside The Revamped R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Factory". Our State. Retrieved 2019-06-05.

- ^ Craver, Richard (2014-06-20). "Old Reynolds sites are economic building blocks". Winston-Salem Journal. Retrieved 2019-06-05.

- ^ Daniel, Fran (2016-03-29). "Wexford to develop portions of Bailey Power Plant at the Innovation Quarter". Winston-Salem Journal. Retrieved 2019-06-05.

- ^ Shapiro, Elise (2019-01-24). "The Bailey Power Plant – The Heart of the Wake Forest Innovation Quarter". Work Design Magazine. Retrieved 2019-06-05.

- ^ "Reynolds Building, Winston-Salem". Emporis. Archived from the original on July 31, 2012. Retrieved 2009-12-03.

- ^ Craver, Richard (2008-10-06). "R.J. Reynolds Tobacco to move out of historic building". Winston-Salem Journal. Archived from the original on 2008-10-09. Retrieved 2009-12-03.

- ^ "Deed to 1100 Reynolds Blvd". Forsyth County Government, Register of Deeds. Retrieved October 25, 2021.

- ^ a b Craver, Richard (2019-10-10). "High-end apartments, restaurant and retail space, 125-room hotel planned for Whitaker Park". Winston Salem Journal. Retrieved 2019-10-17.

- ^ a b c Craver, Richard (2023-08-23). "Major Whitaker Park change: Cook Medical bowing out, Purple Crow stepping in". Winston Salem Journal.

- ^ a b Craver, Richard (2015-01-08). "Iconic Whitaker Park donated to nonprofit". Winston-Salem Journal. p. A1.

- ^ Craver, Richard (2022-03-03). "Whitaker Park revitalization advances with plans for two major facilities". Winston Salem Journal. Retrieved 2022-03-03.

- ^ a b "RJR Moving Into New Headquarters," Twin City Sentinel, September 14, 1977.

- ^ a b c John Cleghorn, "RJR's Farewell Present: Division Moving to Winston-Salem," The Charlotte Observer, July 17, 1987.

- ^ a b c "Wake Forest Debates Use of RJR Gift," The Charlotte Observer, February 7, 1987.

- ^ "RJR Nabisco Plans to Move". The New York Times. 1987-01-16. Retrieved 2012-03-20.

- ^ a b Richard Craver, "For use: a lot of empty space," Winston-Salem Journal, May 30, 2010.

- ^ "RJR Plaza Building". Emporis. Archived from the original on September 3, 2012. Retrieved 2009-12-03.

- ^ Craver, Richard (2009-11-23). "Home of RJR on the market". Winston-Salem Journal. Archived from the original on 2009-11-25. Retrieved 2009-11-23.

- ^ "R.J. Reynolds Tobacco to move out of historic building". The Winston-Salem Journal. 2008-10-06. Retrieved 2012-03-27.

- ^ Craver, Richard (2014-05-22). "Former R.J. Reynolds headquarters sold for $7.8 million". Winston-Salem Journal. Retrieved 2014-05-22.

- ^ Craver, Richard (March 9, 2020). "Truist departing downtown tower will test city's ability to breathe new life into buildings". Winston-Salem Journal. Retrieved March 9, 2020.

- ^ Craver, Richard (2010-12-12). "Wake asks help of city". Winston-Salem Journal. p. A6.

- ^ Craver, Richard (2015-01-08). "Philanthropy stretches across city's landscape". Winston-Salem Journal. p. A1.

- ^ Craver, Richard (April 30, 2024). "Reynolds Tobacco leaf storage buildings up for historic status. Buildings are on 25th Street". Winston-Salem Journal.

Bibliography

[edit]- Collins, Kristin. "Farm union targets RJR". News & Observer. October 27, 2007.

- Tilley, Nannie M. The R. J. Reynolds tobacco company (UNC Press Books, 1985) online, a major scholarly history