Regin

This article relies largely or entirely on a single source. (November 2014) |

In Norse mythology, Reginn ([ˈreɣenː]; often anglicized as Regin or Regan) is a son of Hreiðmarr and the foster father of Sigurð. His brothers are Fáfnir and Ótr.

Attestations

[edit]Völsunga saga

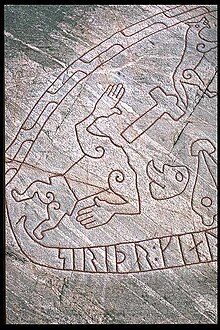

[edit]When Loki mistakenly kills Ótr, Hreiðmarr demands to be repaid with the amount of gold it takes to fill Ótr's skin and cover the outside. Loki takes this gold from the dwarf Andvari, who curses it and especially the ring Andvaranaut. Fáfnir kills his father for this gold, but eventually becomes a greedy worm or dragon. Reginn gets none of the gold, but he becomes smith to the king and foster father to Sigurð, teaching him many languages as well as sports, chess, and runes.[1]

Reginn had all wisdom and deftness of hand. Of his two brothers, he has the ability to work iron as well as silver and gold and he makes many beautiful and useful things. While Sigurð is living with Reginn, Reginn challenges Sigurð's respect in the kingdom. He tells Sigurð to ask for a horse. Sigurð asks the advice of an old man in the forest, and the old man shows him how to get a horse that is descended from Sleipnir, the eight-legged horse of Odin.[2] Reginn continues to goad Sigurð, this time into killing Reginn's brother Fáfnir. He offers to make a sword for Sigurð, but Sigurð broke every sword Reginn forged for him by striking at an anvil. Sigurð retrieves the broken pieces of his father Sigmund's sword, Gram, and brings them to Reginn. Reginn repairs the sword and gives it back to Sigurð. When Sigurð again tests the blade by striking the anvil, the anvil this time is split down to its base, and when Sigurð places a piece of wool in a stream, the current pushing the wool against the sword was enough to cause the blade to cut it in two. Sigurð is finally very pleased with Reginn's repaired weapon.[3]

After using Gram to kill Fáfnir, Sigurð returns to ask Reginn what to do. Reginn instructs him to roast the heart of his brother, and let him eat it. As juice from the dragon's heart foams out, Sigurð tests it with his finger to see if it is done cooking. As the blood touches his tongue, Sigurð understands the speech of birds, who warn him that Reginn intends to kill him. Before he lets any of this happen, Sigurð first wields Gram and cuts off Reginn's head.[4]

Þiðreks saga

[edit]The Norwegian Þiðreks saga relates a slightly different tale, with Reginn as the dragon and Mimir as his brother and foster father to Sigurð.[citation needed]

Reginn the dwarf

[edit]In the 13th century's Poetic Edda (Völuspá 12), the Dvergatal lists Reginn as a dvergr (dwarf).[citation needed]

Among the heroic lays of the Poetic Edda (Reginsmál, aka Sigurðarkviða Fáfnisbana Önnur) says:

- Reginn the son of Hreiðmarr .. was the most skillful of men, and a Dvergr of size. He was wise, dark, and versed in magic.

- Reginn .. var hverjum manni hagari ok dvergr of vöxt. Hann var vitr, grimmr, ok fjölkunnigr.[citation needed]

The Prose Edda (Skáldskaparmál 46) identifies the father of Reginn as Hreiðmarr, and his brothers Fáfnir and Ótr.[citation needed]

Modern influence

[edit]

In the operatic cycle Der Ring des Nibelungen by Richard Wagner, the role of Reginn is played by the Nibelung dwarf Mime, brother of Alberich (the Nibelung who forged the cursed ring out of the Rhinegold). Except for the change in name, probably inspired by the Þiðrekssaga, the story of Reginn, Sigurð, and Fáfnir in Siegfried follows closely the text of the Eddas. However, in this version Mime is unable to reforge the sword Nothung, since only one who does not know fear—such as Siegfried—can do so.[citation needed]

Reginn also appears as the main protagonist of Book V in Fire Emblem Heroes, albeit as a female dwarf as opposed to being male. She is voiced by Megan Shipman.[citation needed]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Byock 1990, p. 56

- ^ Byock 1990, pp. 55–57

- ^ Byock 1990, pp. 59–60

- ^ Byock 1990, pp. 65–66

References

[edit]- Byock, Jesse L. (1990), Saga of the Volsungs: The Norse Epic of Sigurd the Dragon Slayer, Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-23285-2.