National Portrait Gallery (United States)

| |

National Portrait Gallery's F Street entrance | |

Interactive fullscreen map | |

| Established | 1962 |

|---|---|

| Location | Eighth and F Streets, NW, Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Coordinates | 38°53′52″N 77°1′23″W / 38.89778°N 77.02306°W |

| Visitors | 1,069,932 |

| Director | Kim Sajet (2013–present) |

| Public transit access | |

| Website | npg |

The National Portrait Gallery (NPG) is a historic art museum in Washington, D.C., United States. Founded in 1962 and opened in 1968, it is part of the Smithsonian Institution. Its collections focus on images of famous Americans. Along with the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the museum is housed in the historic Old Patent Office Building.

History

[edit]Founding of the museum

[edit]

The first portrait gallery in the United States was Charles Willson Peale's American Pantheon, also known as Peale's Collection of Portraits of American Patriots, established in 1796. It closed after two years. In 1859, the National Portrait Gallery in London opened, but few Americans took notice.[1] The idea of a federally owned national portrait gallery can be traced back to 1886, when Robert C. Winthrope, president of the Massachusetts Historical Society, visited the National Portrait Gallery in London. Upon his return to the United States, Winthrope began pressing for the establishment of a similar museum in the United States.[2]

In January 1919, the Smithsonian Institution entered into a cooperative endeavor with the American Federation of Arts and the American Mission to Negotiate Peace to create a National Art Committee. The committee's goal was to commission portraits of famous leaders from the various nations involved in World War I. Among the committee's members were oil company executive Herbert L. Pratt, Ethel Sperry Crocker, an art aficionado and wife of William Henry Crocker, the founder of Crocker National Bank, architect Abram Garfield, Mary Williamson Averell, wife of railway executive E. H. Harriman, financier J. P. Morgan, attorney Charles Phelps Taft, brother of President William Howard Taft, steel magnate Henry Clay Frick, and paleontologist Charles Doolittle Walcott.[3] The portraits commissioned went on display in the National Museum of Natural History in May 1921. This formed the nucleus of what would become the National Portrait Gallery Collection.[4]

In 1937, Andrew Mellon donated his large collection of classic and modernist art to the United States, which led to the foundation of the National Gallery of Art. The collection included a large number of portraits. Mellon asked that, should a portrait gallery be created, the portraits be transferred to it. David E. Finley, Jr., an attorney and one of Mellon's closest friends, was named the first director of the National Gallery of Art, and he pushed hard over the next several years for the establishment of a portrait gallery.[1]

In 1957, a proposal was made by the federal government to demolish the Old Patent Office Building. After a public outcry and an agreement to save the historic structure, Congress authorized the Smithsonian Institution to use the structure as a museum in March 1958.[5] Shortly thereafter, the Smithsonian Art Commission asked the Chancellor of the Smithsonian to appoint a committee to organize a national portrait museum and to plan for the establishment of this museum in the Old Patent Office Building. This committee was created in 1960.[3]

The National Portrait Gallery (NPG) was authorized and founded by Congress in 1962.[6] The enabling legislation defined its purpose as displaying portraits of "men and women who have made significant contributions to the history, development, and culture of the people of the United States."[6] The legislation specified, however, that the museum's collection be limited to painting, prints, drawings, and engravings.[3][7] Despite the Smithsonian's own extensive collection of art and Mellon's collection, there was very little for the National Portrait Gallery to display. "To found a portrait gallery in the 1960s," Smithsonian Secretary S. Dillon Ripley said, was difficult because "American portraiture has already reached the zenith in price and the nadir in supply."[1] Ripley, whose leadership of the Smithsonian began in 1964, was a strong supporter of the new museum, however. He encouraged the museum's curators to build a collection from scratch based on individual pieces chosen through high-quality scholarship rather than buying complete collections from others. The NPG's collection was slowly built over the next five years through donations and purchases. The museum had little money at this time. Often, it located items it wanted and then asked the owner to simply donate it.[1]

The first NPG exhibit, "Nucleus for a National Collection", went on display in the Arts and Industries Building in 1965 (the bicentennial of James Smithson's birth). The following year, the NPG completed the Catalog of American Portraits, the first inventory of portraiture held by the Smithsonian. The catalog also documented the physical characteristics of each artwork, and its provenance (author, date, ownership, etc.).[3] The museum moved into the Old Patent Office Building with the National Fine Arts Collection in 1966.[8] It opened to the public on October 7, 1968.[9]

Building the collection

[edit]The Old Patent Office Building was renovated in 1969 by the architectural firm of Faulkner, Fryer and Vanderpool. The renovation won the American Institute of Architects National Honor Award in 1970.[10] The following year, the NPG began the National Portrait Survey, an attempt to catalog and photograph all portraits in all formats held by every public and private collection and museum in the country. On July 4, 1973, the NPG opened "The Black Presence in the Era of the American Revolution, 1770–1800", the first exhibit at the museum dedicated solely to African Americans. Philanthropist Paul Mellon donated 761 portraits by French-American engraver C.B.J.F. de Saint-Mémin to the museum in 1974.[3]

Congress passed legislation in January 1976 allowing the National Portrait Gallery to collect portraits in media other than graphic arts.[7] This permitted the NPG to begin collecting photographs. The Library of Congress had long opposed the move in order to protect its own role in collecting photographs, but NPG Director Marvin Sadik fought hard to have the ban eliminated.[1] The NPG rapidly expanded its photography collection, and in October 1976 established a Department of Photographs. The gallery's first photography exhibit, "Facing the Light: Historic American Portrait Daguerreotypes", opened in September 1978.[3] It also continued to build its other collections. In February 1977, the museum acquired an 1880 self-portrait by Mary Cassatt, one of only two painted by her.[3] Eleven months later, the museum acquired a self-portrait by John Singleton Copley. The roundel (a circular canvas), one of only four self-portraits by the celebrated early American artist, was donated to the NPG by the Cafritz Foundation.[11]

In May 1978, Time magazine donated 850 original portraits which had graced its cover between 1928 and 1978.[12] A major exhibit of these pieces debuted in May 1979.[3]

The Stuarts controversy

[edit]

A major controversy occurred in 1979 over the National Portrait Gallery's attempt to buy two Gilbert Stuart paintings. The famous, unfinished portraits of George and Martha Washington were owned by the Boston Athenaeum, which loaned them to the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston in 1876. But the Athenaeum, a private collection, was suffering from financial difficulties by the late 1970s. It twice offered to sell the two portraits to the Museum of Fine Arts over the previous two years, but the museum declined to purchase them. The Athenaeum began searching for another buyer, and in early 1979 the Athenaeum tentatively reached an agreement to sell the works to the NPG for $5 million. When the Athenaeum made these discussions public in April 1979, there was strong public opposition to the sale in Boston.[13]

NPG director Marvin Sadik declined to cancel the sale, arguing that the portraits were of national historic value and belonged in the Smithsonian.[14] A campaign by prominent Bostonians tried to raise $5 million to keep the portraits in Massachusetts.[15] Boston Mayor Kevin H. White sued to keep the portraits in Boston, naming Massachusetts Attorney General Francis X. Bellotti, whose office the Commonwealth's constitution designates "custodian of public property" in the suit. "Everybody knows Washington has no culture—they have to buy it," White said.[16]

On April 12, the Athenaeum and NPG agreed to delay the sale until December 31, 1979, to give the Boston fund-raising effort a chance.[17][18] Although not completely successful, the lawsuit had one effect: Attorney General Bellotti announced in mid-summer that the Stuart portraits could not be sold without his permission.[18] By November 1979, the fund-raising campaign had netted only $885,631, with a pledge from the Museum of Fine Arts to match the amount if necessary.[18] This left the campaign $4 million short of the purchase price. The Athenaeum refused to lower the price, describing the $5 million listing as a significant discount from the portraits' real value.[19]

With public and political pressure on the Smithsonian to resolve the issue, the Museum of Fine Arts and NPG agreed on February 7, 1980, to jointly purchase the portraits. Under the agreement, the paintings would spend three years at the National Portrait Gallery (beginning in July 1980), and then three years in Boston at the Museum of Fine Arts.[20] Attorney General Bellotti approved the plan in March.[21] Per the agreement, the portraits went on display in Washington on July 1, 1980.[22]

NPG director Marvin Sadik, who had expressed his dissatisfaction over the Stuart painting controversy, took a six-month-long sabbatical in January 1981. He announced his retirement from the museum in July.[23]

Expanding the collection

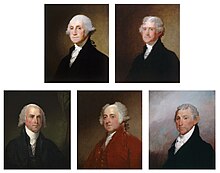

[edit]Even as the Stuarts controversy occupied the attention of the press, the National Portrait Gallery continued to expand its collection. In April 1979, it obtained five other portraits by Gilbert Stuart. These five paintings — of presidents George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, James Monroe, John Adams, and James Madison — were known as the Gibbs-Coolidge set. The portraits were donated by the Coolidge family of Boston (without controversy).[24] In December, the museum obtained a bust of Alexander Hamilton by John Trumbull (which may have been sculpted from the portrait which was later used for the $10 bill) and a Gilbert Stuart portrait of Representative Fisher Ames from the Henry Cabot Lodge family in Massachusetts.[25] The following April, Varina Webb Stewart and Joel A.H. Webb presented important portraits of Jefferson Davis and his wife, Varina Howell Davis, to the National Portrait Gallery. (Stewart and Webb were the Davis' great-grandchildren.)[3] In 1980, the museum obtained (through purchase and loan) a number of works by graphic artist Howard Chandler Christy for exhibit. Works displayed ranged from his "Christy girl" recruiting posters to history-based works such as Scene at the Signing of the Constitution of the United States.[26]

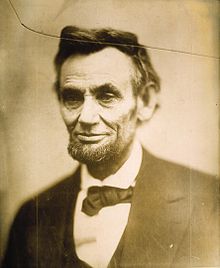

By 1981, the museum had more than 2,000 items in its collection.[23] Two major 19th-century photography collections were added by the museum that year. The first such acquisition was the Frederick Hill Meserve Collection of 5,419 glass negatives produced by the studio of famed Civil War photographer Mathew Brady and his assistants.[27] Using historically accurate chemicals, paper, and techniques, prints were made of the negatives and the prints placed on rotating display. The Washington Post later described the importance of the acquisition by saying it made the NPG the "epicenter" for Brady scholarship.[28] Later that year, 5,400 Civil War-era glass negatives produced by photographer Alexander Gardner were also purchased from the Meserve family. This included the famous "cracked-plate" portrait of Abraham Lincoln taken in February 1865, which was the last photographic portrait of Lincoln taken before his death in April 1865.[3]

Two major portrait purchases were also made in the early 1980s. One was a Gilbert Stuart portrait of Thomas Jefferson, for which the museum paid $1 million to a private collector. A portion of the purchase price came from the Thomas Jefferson Foundation, which owns and operates Jefferson's historic plantation home of Monticello. The two parties agreed have the portrait spend time at both locations.[29] The second major purchase was an Edgar Degas portrait of his friend, Mary Cassatt, for which the museum paid $1.3 million.[30]

The museum suffered a major theft in 1984 — although it was not a portrait. On December 31, 1984, a thief pried open a display case and stole four handwritten documents accompanying several portraits of Civil War generals. One of the documents was written and signed by President Abraham Lincoln. The remaining three were written and signed by Civil War generals Ulysses S. Grant, George Meade, and George Armstrong Custer. The FBI was contacted and worked with Smithsonian police to investigate the crime. Within two weeks, a historic documents dealer contacted the FBI and said he had been offered the documents for sale. On February 8, 1985, police arrested Norman James Chandler, a part-time mechanic's assistant from Maryland, for the theft. Chandler quickly pleaded guilty. He was sentenced in April 1985 to two years in jail (with all but six months suspended) and two years of probation, and required to pay a $2,000 fine.[31] All four documents were recovered.[32]

The late 1980s saw the collection continue to expand, although there were fewer major additions. One significant acquisition was a nude image — a self-portrait painting by Alice Neel acquired in 1985. It was the National Portrait Gallery's first nude work. Neel was 80 years old when she painted it.[3] Two years later, noted photographer Irving Penn donated 120 platinum prints of fashion and celebrity portraits he produced over the past 50 years.[33]

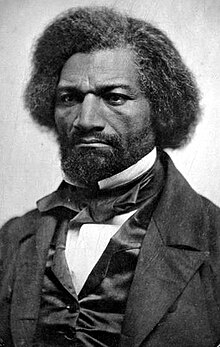

Two very important daguerreotypes (an early photographic process) were purchased in the 1990s. The first was of African American abolitionist and former slave Frederick Douglass, acquired in 1990. It is one of only four daguerreotypes of Douglass known to exist. That year, the number of images in the museum's photography collection reached 8,500 objects.[34] Six years later, the NPG obtained for $115,000 the earliest known daguerreotype of abolitionist John Brown, whose 1859 raid on Harpers Ferry helped to spark the Civil War. The portrait was created by African American photographer Augustus Washington.[35]

Purchasing the Lansdowne portrait

[edit]

In the fall of 2000, Neil Primrose, 7th Earl of Rosebery, offered to sell Gilbert Stuart's Lansdowne portrait of George Washington to the National Portrait Gallery. The painting was commissioned in April 1796 by Senator William Bingham of Pennsylvania—one of the wealthiest men in America at the time. The 8 by 5 feet (2.4 by 1.5 m) portrait was given as a gift to British Prime Minister William Petty FitzMaurice. FitzMaurice was the 2nd Earl of Shelburne, and later became the first Marquess of Lansdowne (hence the name of the portrait). Lansdowne died in 1805, and in 1890 the painting was purchased by the 5th Earl of Rosebery. The Lansdowne portrait was displayed only three times in the United States (although several copies remained in America). On its third trip in 1968, it was exhibited by the National Portrait Gallery, and it remained there on indefinite loan. Lord Rosebery offered to sell the painting for $20 million, a price at the low end of estimates. But the offer came with a deadline of April 1, 2001. A search for a donor, personally led by Smithsonian Secretary Lawrence Small and the Smithsonian's Board of Regents, proved fruitless after three months. Worried Smithsonian officials then went public in February 2001 with a plea for a donor to come forth.[36]

On March 13, just two weeks before the sale deadline, the Donald W. Reynolds Foundation donated $30 million to buy the Lansdowne portrait. Foundation chairman Fred W. Smith read about failing donor effort in the Wall Street Journal on February 26. Although the Reynolds Foundation generally only made grants in the areas of elder care, cardiovascular research, and journalism, assisting with the Lansdowne purchase fell within the foundation's "special projects" area of responsibility.[37] NPG Director Marc Pachter flew to Nevada to meet with foundation officials on March 3, and the foundation approved the donation the following day. The $30 million donation included $6 million to put the portrait on a national tour for three years (the NPG was closed for renovations until 2006), and $4 million to construct a new area in the Old Patent Office Building to display it. NPG said it would name this display area for Donald W. Reynolds, the media baron who created the foundation.[38]

Post-renovation activities

[edit]The National Portrait Gallery closed in January 2000 for a renovation of the Old Patent Office Building. Intended to take two years and cost $42 million, the renovation took seven years and cost $283 million. Inflation, delays in obtaining approval for the renovation design, the addition of a glass canopy over the open courtyard, and other issues led to increases in both time and costs. During this period, most of the NPG's collection went on tour around the United States.

In March 2007, a multi-year study of leadership at eight Smithsonian museums made recommendations about the National Portrait Gallery. The report concluded that the museum needed stronger, more visionary leadership intent on creating a truly national museum. The report also called for "administrative consolidation" of the National Portrait Gallery and the Smithsonian American Art Museum.[39]

After the 2008 presidential election, the National Portrait Gallery obtained graphic artist Shepard Fairey's ubiquitous "Hope" poster of Barack Obama. Obama supporter Tony Podesta and his wife, Heather, donated it to the museum.[40]

Hide/Seek controversy

[edit]In November 2010, the National Portrait Gallery hosted a major new exhibit, "Hide/Seek: Difference and Desire in American Portraiture", curated by David C. Ward and Jonathan Katz. The exhibit focused on depictions of homosexual love through history, and was the first exhibit hosted by a museum of national stature to address the topic.[41] It was also the largest and most expensive exhibit in the NPG's history, and more private donors contributed to it than to any prior NPG exhibit.[42] Included in the 105 pieces in the exhibit was a four-minute, edited version of artist David Wojnarowicz's short silent film A Fire in My Belly. Eleven seconds of the video depicted a crucifix covered in ants.[42]

The exhibit was scheduled to run from October 30, 2010, to February 13, 2011. Within days of its opening, Catholic League president William A. Donohue labeled A Fire in My Belly hate speech, anti-Catholic, and anti-Christian. A spokesperson for Representative John Boehner, incoming Speaker of the United States House of Representatives, called it an "arrogant" abuse of the public trust and a misuse of taxpayer money, although it was funded by private donations.[42][43] House Majority Leader Representative Eric Cantor threatened to reduce the Smithsonian's budget if the film remained on view.[44] After consulting with National Portrait Gallery director Martin Sullivan, co-curator David C. Ward (but not with co-curator Jonathan David Katz),[45] Smithsonian Undersecretary Richard Kurin, and the Smithsonian's government affairs and public relations offices, Smithsonian Secretary G. Wayne Clough ordered A Fire in My Belly removed from the exhibit on November 30.[42]

Clough's decision led to extensive accusations of censorship and claims that the Smithsonian was caving in to pressure from a small group of vocal activists. Smithsonian officials strongly defended the video's removal. "The decision wasn't caving in," said Sullivan. "We don't want to shy away from anything that is controversial, but we want to focus on the museum's and this show's strengths."[42] Kurin expressed the Smithsonian's desire to be responsive to public opinion, but also emphasized the remaining exhibit's importance. "We are sensitive to what the public thinks about our shows and programs," he said. "We stand behind the show. It has strong scholarship with great pieces by artists who are recognized by a whole panoply of experts. It represents a segment of America."[42] On December 13, the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, one of the principal sponsors of the exhibit, said it would ask for its $100,000 donation back if the film was not restored. Clough replied, "...the Smithsonian's decision to remove the video was a difficult one and we stand by it." The donation was returned, and the Warhol Foundation ceased to support National Portrait Gallery exhibits.[46] The Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation, which donated $10,000 to support the exhibit, also ended all funding for future Smithsonian exhibitions. Both decisions drew criticism from some gay rights supporters, who felt the funding cuts were too draconian since the remainder of the pieces continued to be exhibited.[47]

The controversy lasted through the exhibit's scheduled run. In late January 2011, the Smithsonian Board of Regents unanimously gave Clough a vote of confidence, saying his accomplishments in improving the Smithsonian's administration, finances, governance, and maintenance in the past 19 months far outweighed the damage done by the "Hide/Seek" controversy. Clough admitted, however, that he may have acted too hastily in the matter (although he continued to say he made the right decision), and the regents asked for Smithsonian staff to study the controversy and report back on how to handle such events in the future. Not everyone in the Smithsonian agreed with the regents. The Washington Post reported that some (unnamed) Smithsonian museum directors and curators felt there would be a chilling effect from Clough's decision. The Board of Directors of the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden wrote an open letter to Clough in which they said they were "deeply troubled by the precedent" to remove the film.[48]

Outwin Boochever Portrait Competition

[edit]In 2006, the museum began hosting a triennial, juried contemporary portrait exhibition called the Outwin Boochever Portrait Competition. Named after long time docent and volunteer Virginia Outwin Boochever, this competition is widely regarded[who?] as the most prestigious portrait competition in the United States.[citation needed] Artists working in the fields of painting, drawing, sculpture, photography, and other media are allowed to enter.[49] Works must be created through a face-to-face encounter with the subject.[50] The inaugural competition in 2006 drew more than 4000 entries, from which 51 finalists were chosen. For the 2013 competition the total prize money of $42,000 was awarded to the top eight commended artists, and the winner received $25,000 and a commission to make a portrait for the museum's permanent collection.[51] The subject of the commission is decided jointly by the artist and the NPG curators. The 2006 winner was David Lenz of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and he was commissioned to paint a portrait of Eunice Kennedy Shriver, the founder of Special Olympics. It was the first portrait commissioned of an individual who has not served as a president or first lady.[52] The 2009 winner, Dave Woody of Fort Collins, Colorado,[53] was commissioned to photograph food pioneer Alice Waters, founder of the Chez Panisse Restaurant and Cafe, the Edible Schoolyard and champion of the Slow Food movement. The 2013 winner was Bo Gehring of Beacon, New York,[54] who was commissioned to direct a video portrait of jazz musician Esperanza Spalding.[55]

Post-2010 exhibits of note

[edit]In 2012, the National Portrait Gallery sponsored a new temporary exhibit, "Poetic Likeness: Modern American Poets", which focused on images of great American poets. The NPG collection had grown so large that the exhibit drew its images almost entirely from the museum's own collection.[56]

Collection

[edit]

As of 2011, the National Portrait Gallery was the only museum in the United States dedicated solely to portraiture.[6] The museum had 65 employees and a $9 million annual budget in 2013. By February 2013, it housed 21,200 works of art, which had been seen by 1,069,932 visitors in 2012.[57]

Portrait addition procedure

[edit]By 1977, the National Portrait Gallery had three curatorial divisions: Painting and sculpture, prints and drawings, and photography.[1]

Initially, the National Portrait Gallery had fairly strict rules regarding which images could enter its collection. The person depicted had to be historically significant. An individual also needed to be dead at least 10 years before their portrait could be displayed (although some images of obviously important living people were acquired while they still lived). After an initial affirmative determination by curators at a monthly curatorial meeting, the National Portrait Gallery Commission (the museum's board of directors) approved the person's inclusion. The commission was initially quite conservative in its assessment of "historically significant", although this position began to be more relaxed by 1969.[1] As of 2006, the definition of "historically significant" had become quite loose, although "some kind of fame or notoriety remains a prerequisite". Portraits of living individuals or those dead less than 10 years are also now allowed to be displayed in the museum, as long as their inclusion is clearly important (such as presidents or generals).[58][59]

The process for choosing which images the museum acquires is simple but can be contentious. Potential acquisitions are vigorously and informally discussed at length by researchers, historians, and the curatorial departments. Some of the criteria used in the decision-making process are: The number of existing portraits of the individual already in the collection, the quality of the potential portrait, the uniqueness of the potential portrait, the reputation of the portrait's author, and the cost of the portrait. Formal decisions to acquire a portrait are made at monthly curatorial meetings, then ratified by the National Portrait Gallery Commission.[1]

Key exhibits and programs of the museum

[edit]

A hallmark of the National Portrait Gallery's permanent collection is the Hall of Presidents, which contains portraits of nearly all American presidents. It is the largest and most complete collection in the world, except for the White House collection itself.[60] The centerpiece of the Hall of Presidents is the famous Lansdowne portrait of George Washington. How the museum obtains presidential images has changed over the years. Presidential portraits from 1962 to 1987 were usually obtained through purchase or donation. Beginning in 1998, NPG began commissioning portraits of presidents, starting with George H. W. Bush. In 2000, NPG began commissioning portraits of First Ladies as well, beginning with Hillary Clinton. Funds for these commissions are privately raised, and each portrait costs about $150,000 to $200,000.[60] Former president Trump has used his Save America PAC to pay $650,000 for portraits of him and the former first lady that will one day hang in the National Portrait Gallery.[61][62][63]

The museum's more notable art pieces include:[a][3][11][21][24][25][29][30][34][35][40][57][64]

- "Abraham Lincoln" (glass plate, cracked; 1865) by Alexander Gardner

- "Alexander Hamilton" (bust, 1789) by John Trumbull

- "Beauford Delaney" (1940) by Georgia O'Keeffe

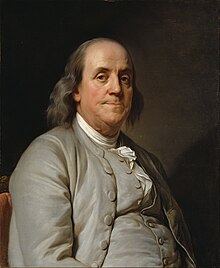

- "Benjamin Franklin" (c. 1785) by Joseph Duplessis

- "Charlie Chaplin" (1925) by Edward Steichen

- "Colin Powell" (2012) by Ron Sherr

- "Donald Trump" (photo, 1989) by Michael O'Brien[65][66]

- "Ethel Waters" (1940) by Beauford Delaney

- "Eunice Kennedy Shriver" (2009) by David Lenz[67]

- "Frederick Douglass" (daguerreotype, 1856) by unknown artist

- "George Washington" (unfinished, 1796) by Gilbert Stuart

- "Henry Cabot Lodge" (1890) by John Singer Sargent

- "Hope" (Barack Obama) (2008) by Shepard Fairey

- "Jefferson Davis" (1849) by George Lethbridge Saunders

- "John Adams" (1800–1815) by Gilbert Stuart

- "John Brown" (daguerreotype, 1846–1847) by Augustus Washington

- Lansdowne portrait (George Washington) (1796) by Gilbert Stuart

- "Martha Washington" (unfinished, 1796) by Gilbert Stuart

- "Mary Cassatt" (1880–1884) by Edgar Degas

- "Osceola" (1804–1838) by George Catlin

- "Self-Portrait" (1880) by Mary Cassatt

- "Self-Portrait" (1880–1881) by Paul Cézanne

- "Self-Portrait" (1780–1784) by John Singleton Copley

- "Thomas Jefferson" (1805) by Gilbert Stuart

- "Varina Howell Davis" (1849) by John Wood Dodge

- "Barack Obama" (2018) by Kehinde Wiley

Among the museum's more prominent collections are:[3][26][27][33][57]

- Alexander Gardner (photography)

- Howard Chandler Christy (graphic arts)

- Irving Penn (photography)

- Mathew Brady (photography)

- Time magazine covers (graphic arts)

Building

[edit]

The National Portrait Gallery occupies a portion of the Old Patent Office Building, a National Historic Landmark. The building is located just south of Chinatown in downtown Washington. Constructed between 1836 and 1867,[68] the building has a sandstone and marble façade,[69] and porticoes modeled after the Parthenon.[70]

The building was used as a hospital during the American Civil War, and both Clara Barton and Walt Whitman worked as nurses there.[71] The Bureau of Indian Affairs, the United States General Land Office, and the Bureau of Pensions jointly occupied the building with the Patent Office through the Civil War and into the post-war period.[72] The massive increase in pension processing required by the Civil War led to the construction of a new Pension Bureau Building into which the Bureau of Pensions moved in 1887.[73] The General Land Office and the Bureau of Indian Affairs vacated the building in 1898.[74] The United States Civil Service Commission and the Government Accounting Office occupied the building after the Patent Office vacated it in 1932.[75] The Government Accounting Office vacated the structure in 1942, after its new headquarters nearby was complete.[76] The Civil Service Commission began constructing its own headquarters, and planned to vacate the building in 1962.[77]

Local D.C. businessmen asked the General Services Administration (GSA) to tear down the building and sell the land so a private parking garage could be built on the centrally located site. Legislation for this purpose was introduced in Congress in the waning days of the 82nd United States Congress in 1952, but did not pass. The legislation encountered resistance from a few members of Congress, architects, and the influential Committee of 100 on the Federal City (a non-profit advocate for responsible planning and land use).[78] GSA reversed course and said in June 1956 it no longer wanted to demolish the building. However, the agency said it would continue to use it for federal office space (which was in short supply) until the Civil Service Commission vacated the structure.[79] On March 21, 1958, Congress unanimously passed legislation authorizing the transfer of the building to the Smithsonian for a national art museum.[80] President Dwight Eisenhower signed the legislation a few days later.[81]

Congress passed legislation establishing the National Portrait Gallery in 1962, and the Civil Service Commission moved out of the structure in November 1963.[82] Preparations for the renovation began in November 1964,[83] and the Grunley, Walsh Construction Co. began demolition of non-historic interior structures by May 1965.[84] The $6 million renovation was complete by April 1968,[85] and the National Portrait Gallery opened on October 7.[86]

2000 to 2007 renovation

[edit]

In 1995, the Smithsonian revealed that the Old Patent Office Building was in serious disrepair.[87] The Smithsonian announced in January 1997 that the building would close in January 2000 for a two-year, $42 million renovation. Hartman-Cox Architects was hired to oversee the conservation and repair.[88] But just three years later, as the renovation was about to begin, the cost of repairs had risen to $110 million to $120 million.[89]

Prior to the building's closure in January 2000, a decision was reached to allot about one-third of the building's total space to the National Portrait Gallery while simultaneously eliminating the informal north–south division between the NPG and American Art Museum.[90] This led to acrimony between the two museums, and a public debate about which collection deserved more space. The Smithsonian resolved the dispute practically: Art that best fit an exhibition space got it. (For example, since modern art often tends toward large canvases, this art is on the high-ceilinged third floor.)[59]

The cost of the renovation rose to $180 million by March 2001. That month, Nan Tucker McEvoy (a California newspaper heiress and arts patron) donated $10 million for the renovation.[91] The Henry Luce Foundation gave another $10 million later that year.[92] Costs continued to rise. Although Congress appropriated $33.5 million for the renovation, reconstruction costs were estimated at $214 million in June 2001 and the museum not scheduled to reopen until 2005.[93] Just a month later, the reopening was pushed back even further to July 2006.[94]

In 2003, the government increased its contribution to $166 million. Smithsonian officials subsequently began discussing a major change to the renovation design: Adding a glass roof to the open courtyard in the center of the Old Patent Office Building. Congress approved the change in August 2003. In March 2004, the Smithsonian announced that architect Norman Foster, would design the glass canopy.[95] In November, Robert Kogod (a real estate development executive) and his wife, Arlene (heiress to Charles E. Smith Construction fortune) donated $25 million to complete the canopy. By then, costs had risen to $298 million. $60 million in private funds still needed to be raised.[92] Today, the Kogod Courtyard is a popular meeting place in DC. There is plenty of seating, free wifi, and a cafe[96] with snacks for museum visitors open from 11:30 am until 6:30 pm.

Design approval for the canopy proved difficult. The design had to be approved by the National Capital Planning Commission (NCPC), which has statutory authority to approve all buildings and renovations in the D.C. metropolitan area. Although the NCPC approved the preliminary design,[92] the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation (ACHP), the United States Department of the Interior, the D.C. State Preservation Office, and the National Trust for Historic Preservation all opposed the enclosure of the courtyard.[97] The NCPC reversed its preliminary approval on June 2, 2005.[98] Unwilling to lose the canopy, the Smithsonian brought five alternatives to the NCPC on August 4.[99] On September 8, 2005, the NCPC reversed itself yet again, and approved one of the revised designs.[100] The delay cost the Smithsonian $10 million.[59] In October 2005, the Donald W. Reynolds Foundation made a $45 million donation to the NPG to finish both the building renovation and the canopy.[101] The Smithsonian agreed to call the two museums, the conservation center, courtyard, storage facility, and other operations within the Old Patent Office complex the "Donald W. Reynolds Center for American Art and Portraiture" in appreciation for the gift.[102] The National Portrait Gallery reopened on July 1, 2006.[103] The total cost of the building's renovation was $283 million.[104]

Attendance at the renovated building rose significantly to 214,495 in just two months. In the past, both museums had drawn just 450,000 over 12 months. The achievement was even more impressive in the face of flat or declining attendance at all other Smithsonian museums.[105] The higher attendance was not all positive. Some patrons spit on art they did not like, while others kissed or touched some paintings. Video security cameras were hastily installed in September 2007 to stop the vandalism.[106] By the end of the year, more than 786,000 people had visited the two museums.[107]

Governance and directors

[edit]The National Portrait Gallery is governed by a board of directors known as the National Portrait Gallery Commission. The commission members are appointed by the Regents of the Smithsonian Institution. The museum is led by a Director, who oversees its day-to-day activities. Directors of the museum include:

- Charles Nagel – July 1, 1964 – 1969

- Marvin Sadik – 1969 – July 1981[23]

- Alan M. Fern – June 1982 – 2000[108]

- Marc Pachter – 2000–2007[109]

- Martin E. Sullivan – 2008–2012[110]

- Wendy Wick Reaves – 2012–2013 (interim)

- Kim Sajet – April 2013–[111]

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Images are paintings, drawings, or similar media, unless otherwise noted.

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h Thompson, Bob. "Who Gets Into the National Portrait Gallery, and Why?" Washington Post. June 13, 1999.

- ^ Smith, p. 268.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "Chronology of the National Portrait Gallery". Smithsonian Institution Research Information System. 2012. Archived from the original on November 29, 2014. Retrieved February 5, 2013.[better source needed]

- ^ Oehser, p. 146.

- ^ Oehser, p. 200.

- ^ a b c Schultz, p. 272.

- ^ a b Richard, Paul. "A New Face for the Stuffy Old Portrait". Washington Post. April 3, 1977.

- ^ Alexander, p. 302.

- ^ Richard, Paul. "A National Family Album". Washington Post. October 6, 1968; Martin, Judith. "'Semi, Demi-Heroes' Open New Gallery." Washington Post. October 7, 1968.

- ^ "Avery C. Faulkner". Wilmington Star-News. February 25, 2007.

- ^ a b Richard, Paul. "American Masterwork: Portrait Gallery's New 'Cornerstone' A Copley Self-Portrait for the Portrait Gallery". Washington Post. January 16, 1978.

- ^ Permanent Collection Illustrated Checklist, p. 7.

- ^ Glueck, Grace. "Athenaeum's Dilemma". New York Times. April 6, 1979; "Free George and Martha". Washington Post. April 9, 1979.

- ^ Richard, Paul. "Marvin Sadik: 'I'm Resolute'". Washington Post. April 11, 1979.

- ^ Cowen, Peter. "For $5m, Portraits Stay Here". Boston Globe. April 12, 1979.

- ^ Knight, Michael. "Boston City Officials Go to Court to Keep 2 Washington Portraits". New York Times. April 11, 1979.

- ^ Richard, Paul. "Bound in Boston". Washington Post. April 13, 1979.

- ^ a b c "Bostonians Are Falling Short in Drive to Keep Art". Associated Press. November 25, 1979.

- ^ "Portrait Fund Drive Falls $4 Million Short". Washington Post. January 18, 1980.

- ^ "Museums in Capital and Boston to Share Washington Portraits". New York Times. February 8, 1980; "Museums Come to Terms on Stuarts". Washington Post. February 23, 1980.

- ^ a b "Pact on Stuarts Approved By Massachusetts Official". Associated Press. March 22, 1980; "Stuart Portraits Plan Wins Tentative Approval". Washington Post. March 24, 1980.

- ^ Rosenfeld, Megan. "New Faces in Town". Washington Post. June 24, 1980; Radcliffe, Donnie. "Back In the Picture". Washington Post. July 4, 1980.

- ^ a b c "Sadik, Director, Quits National Portrait Gallery". New York Times. June 1, 1981. Retrieved February 5, 2013.

- ^ a b Glueck, Grace. "5 Stuarts Go to U.S. Gallery". Washington Post. April 10, 1979.

- ^ a b Richard, Paul. "Lodge Donates Two Portraits". Washington Post. December 15, 1979.

- ^ a b Kernan, Michael. "GEE!! It's Christy". Washington Post. January 11, 1980; "The Loving Eye That Created the Christy Girl". Washington Post. January 11, 1980.

- ^ a b Ostrow, Joanne. "The Meserves' Photo Legacy". Washington Post. May 14, 1982.

- ^ Trescott, Jacqueline. "The Photographer Who Went to War". Washington Post. November 7, 2010.

- ^ a b Richard, Paul. "Gilbert Stuart's Jefferson Acquired for $1 Million". Washington Post. September 10, 1982.

- ^ a b Richard, Paul. "Portrait Gallery Buys Degas." Washington Post. May 22, 1984.

- ^ "Civil War Era Notes Are Stolen". Washington Post. January 1, 1985; Ringle, Ken. "FBI Probes Theft of Notes From Gallery". Washington Post. January 2, 1985; Barker, Karyn. "FBI Arrests D.C. Man in Lincoln Letter Case". Washington Post. February 9, 1985; "Man Sentenced For Stealing Notes From Civil War Era". Washington Post. April 24, 1985.

- ^ "Man Gets 6 Months for Stealing Documents". Associated Press. April 24, 1985. Retrieved February 7, 2013.[dead link]

- ^ a b Grundberg, Andy. "The Beautiful Peoples". Washington Post. June 19, 2005.

- ^ a b "Daguerreotype of Frederick Douglass". Washington Post. December 23, 1990.

- ^ a b Ringle, Ken. "John Brown, Captured For History". Washington Post. December 19, 1996.

- ^ Trescott, Jacqueline. "Smithsonian Battles to Keep Prized Portrait of Washington". Washington Post. February 23, 2001.

- ^ The Reynolds Foundation board had discretion to make grants in areas that presented patriotic or entrepreneurial opportunities or which supported a lifetime interest of foundation founder Donald W. Reynolds.

- ^ Trescott, Jacqueline. "A Washington Bailout." Washington Post. March 14, 2001.

- ^ Farhi, Paul. "Committee Sees a Lack of Money, Leadership at 8 Smithsonian Museums". Washington Post. March 21, 2007.

- ^ a b Argetsinger, Amy and Roberts, Roxanne. "Fit for a T: New at the Portrait Gallery". Washington Post. January 7, 2009.

- ^ Gopnik, Blake. "'Hide/Seek' Finds a Frame for Showing Sexual Identity". Washington Post. November 5, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f Trescott, Jacqueline. "Portrait Gallery Removes Crucifix Video From Exhibit After Complaints". Washington Post. December 1, 2010.

- ^ Almost no taxpayer money was spent on the exhibit, since it was funded by private donations.

- ^ Trescott, Jacqueline. "Clough Defends Removal of Video". Washington Post. January 19, 2011.

- ^ Trescott, Jacqueline. "After Smithsonian Exhibit's Removal, Banned Ant Video Still Creeps Into Gallery". Washington Post. December 6, 2010.

- ^ Trescott, Jacqueline. "'Hide/Seek' Sponsor Threatens to Cut Funding for Smithsonian." Washington Post. December 14, 2010; Taylor, Kate. "Foundation Says It's Ending Smithsonian Support". New York Times. December 13, 2010.

- ^ Capps, Kriston (December 17, 2010). "Mapplethorpe Foundation Withdraws Support for Smithsonian Exhibitions". Washington City Paper. Retrieved February 6, 2013.

- ^ Trescott, Jacqueline. "Regents Support Censorship Decision". Washington Post. February 1, 2011.

- ^ Gopnik, Blake. "Portrait Capital." Washington Post. May 29, 2005.

- ^ Gambino, Megan (October 25, 2011). "Last Call: Outwin Boochever Portrait Competition". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved February 8, 2013.

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions: National Portrait Gallery". Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on May 15, 2013. Retrieved June 7, 2013.

- ^ Sanford, Barbara (May 11, 2009). "Eunice Kennedy Shriver Portrait Unveiled". Smithsonian Magazine.

- ^ "National Portrait Gallery's Portrait Competition". PBS Newshour. November 5, 2009.

- ^ Kennicott, Philip (March 22, 2013). "Boochever Portrait Competition winners". Washington Post.

- ^ Bloom, Benjamin (November 19, 2014). "Bo Gehring: Reminding Us to Slow Down". The Outwin: American Portraiture Today. National Portrait Gallery. Archived from the original on March 11, 2016. Retrieved March 10, 2016.

- ^ Kennicott, Philip. "American Poets, On the Surface." Washington Post. November 4, 2012.

- ^ a b c "Fact Sheets: National Portrait Gallery". Smithsonian Institution. February 1, 2013. Retrieved February 6, 2013.

- ^ Thompson, Bob. "The Changing Face of American Portraiture." Washington Post. June 25, 2006.

- ^ a b c Trescott, Jacqueline. "Museums Reopen to a Brand-New View." Washington Post. July 1, 2006.

- ^ a b Copeland, Libby. "The Clintons: They've Been Framed!" Washington Post. April 25, 2006.

- ^ [1]

- ^ Levinthal, Dave. "Trump PAC's $650,000 'charitable contribution' to the Smithsonian will pay for portraits of Donald and Melania Trump". Business Insider.

- ^ "Donald Trump used $650,000 in supporter money to fund official portrait: documents". The Independent. August 22, 2022.

- ^ Trescott, Jacqueline. "Have Renovation, Will Travel." Washington Post. December 14, 2005.

- ^ Harlan, Becky (January 13, 2017). "National Portrait Gallery Installs Photo Of President-Elect Trump". NPR.org. Retrieved January 17, 2017.

- ^ Mcgraw, Meridith (January 16, 2017). "Trump Photograph Installed at the National Portrait Gallery". ABC News. Retrieved January 17, 2017.

- ^ "National Portrait Gallery Annual Report" [2] October 1, 2008 – September 30, 2009. p. 4,15,back cover.

- ^ Price and Price, p. 102; Silber, p. 61; Acker, p. 14, accessed 2013-02-08.

- ^ Ross, p. 87.

- ^ Sandler, p. 51.

- ^ Dale, p. 47.

- ^ Fixico, p. 27; Bureau of Land Management, p. 25; National Park Service, p. 8.

- ^ Moeller and Feldblyum, p. 100.

- ^ Secretary of the Interior, 1899, p. 107.

- ^ Public Buildings Commission, p. 24-27.

- ^ Committee on Appopriations, p. 466.

- ^ Select Subcommittee on Education, p. 159.

- ^ "Sen. Maybanks Fights Plan to Raze CSC Building." Washington Post. November 17, 1953; "Architects Fight Plan to Raze CSC Building." Washington Post. February 24, 1954; "Committee Protests Razing Plan." Washington Post. December 17, 1955.

- ^ "GSA Wants to Preserve Patent Bldg." Washington Post. June 3, 1956.

- ^ "CSC Building to Become Art Museum." Washington Post. March 22, 1958.

- ^ Sampson, Paul. "Exhibit to Tell American Art Story." Washington Post. April 2, 1958.

- ^ Doolittle, Jerry. "Civil Service Dedicates Home." Washington Post. November 13, 1963.

- ^ Scott, David W. "Patent Building to Become Arty." Washington Post. December 27, 1964.

- ^ Hailey, Jean R. "Art Collection to Go in Old Patent Office." Washington Post. May 21, 1965.

- ^ Richard, Paul. "A Major New Art Museum to Open." Washington Post. April 28, 1968.

- ^ Richard, Paul. "A National Family Album." Washington Post. October 6, 1968.

- ^ Trescott, Jacqueline. "The Dilapidated State of the Nation's Attic." Washington Post. June 10, 1995.

- ^ Lewis, Jo Ann. "Repairs to Close Two Art Museums." Washington Post. January 29, 1997.

- ^ Trescott, Jacqueline. "Extensive Leaks In the Nation's Attic." Washington Post. April 1, 2000.

- ^ Forgey, Benjamin. "The Old Patent Office, Pending Renewal." Washington Post. January 1, 2000.

- ^ Trescott, Jacqueline. "Smithsonian Art Museum Gets Second $10 Million." Washington Post. March 7, 2001.

- ^ a b c Trescott, Jacqueline. "Old Patent Office Gets A $25 Million Boost." Washington Post. November 16, 2004.

- ^ Trescott, Jacqueline. "Smithsonian Projects Face Delays." Washington Post. June 23, 2001.

- ^ Forgey, Benjamin. "Naked Splendor." Washington Post. July 20, 2003.

- ^ Zach Mortice (December 21, 2007). "Museum Courtyard Glides Through the Ages". AIArchitect. Archived from the original on January 1, 2013. Retrieved September 17, 2010; Epstein, Edward (July 2, 2006). "Portrait of a new Washington / Penn Quarter: District of Columbia's once-derelict neighborhood welcomes back Smithsonian museums, tourists with rejuvenated flair". The San Francisco Chronicle; Trescott, Jacqueline. "Way Clear for British Architect's Glass Act". Washington Post. March 16, 2004.

- ^ sysadmin (August 21, 2015). "The Courtyard Café". npg.si.edu. Retrieved October 2, 2019.

- ^ Trescott, Jacqueline. "Patent Office Roof: Pending." Washington Post. April 25, 2005.

- ^ Forgey, Benjamin. "Panel Rejects Smithsonian Plan For Patent Office." Washington Post. June 3, 2005.

- ^ Trescott, Jacqueline. "Old Patent Office Options Clearly Still Favor Glass." Washington Post. August 5, 2005.

- ^ Forgey, Benjamin. "A Roof That's Patently the Best Option." Washington Post. September 9, 2005.

- ^ Trescott, Jacqueline. "Smithsonian Scores a $45 Million Gift." Washington Post. October 12, 2005.

- ^ Trescott, Jacqueline. "Smithsonian Thanks Its Big Donor By Name." Washington Post. October 13, 2005.

- ^ "'Looking History in the Eye' at Portrait Gallery". National Public Radio. July 13, 2006. Retrieved September 18, 2010.

- ^ Philip Kennicott (November 19, 2007). "Seeing the Light at Last". The Washington Post. Retrieved January 15, 2016.

- ^ Trescott, Jacqueline. "Smithsonian Attendance Down." Washington Post. September 20, 2006.

- ^ Grimaldi, James V. (September 29, 2007). "GAO Faults Smithsonian Upkeep and Security". Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 15, 2018.

- ^ Trescott, Jacqueline. "Some People Would Die to Wind Up at This Museum". Washington Post. May 23, 2008.

- ^ "Portrait Gallery Chief Alan Fern to Retire". Washingtonpost.com. February 4, 2000. Retrieved December 3, 2010.

- ^ Jacqueline Trescott (December 12, 2006). "Portrait Gallery Director to Retire in '07". The Washington Post.

- ^ Trescott, Jacqueline (May 7, 2012). "Martin Sullivan Steps Down as Portrait Gallery Director". Washington Post. Retrieved February 5, 2013.

- ^ Boyle, Katherine (February 5, 2013). "National Portrait Gallery Names Kim Sajet as Its New Director". Washington Post. Retrieved February 5, 2013.

Bibliography

[edit]- Acker, William B. Memorandum History of the Department of the Interior. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior, 1913.

- Alexander, Edward P. Museum Masters: Their Museums and Their Influence. Walnut Creek, Calif.: AltaMira Press, 1995.

- Bureau of Land Management. Landmarks in Public Land Management. Department of the Interior. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1962.

- Committee on Appropriations. First Supplemental Civil Functions Appropriation Bill for 1941. Hearings Before the Subcommittee of the Committee on Appopriations. Committee on Appropriations. U.S. House of Representatives. 76th Cong., 3d sess. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1940.

- Dale, Alzina Stone. Mystery Reader's Walking Guide, Washington, D.C. Lincoln, Neb.: IUniverse, 1998.

- Fixico, Donald Lee. Bureau of Indian Affairs. Santa Barbara, Calif.: Greenwood, 2012.

- Moeller, Gerard Martin and Feldblyum, Boris. AIA Guide to the Architecture of Washington, D.C. Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012.

- National Park Service. Report of the Director of the National Park Service to the Secretary of the Interior for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1924. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1924.

- Oehser, Paul H. The Smithsonian Institution. New York: Praeger Publishers, 1970.

- Permanent Collection Illustrated Checklist. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1980.

- Price, Tom and Price, Susan Crites. Frommer's Irreverent Guide to Washington, D.C. Hoboken, N.J.: Wiley Publishing, 2007.

- Public Buildings Commission. Annual Report of the Public Buildings Commission for the Calendar Year 1932. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1933.

- Ross, Betty. A Museum Guide to Washington, D.C. Washington, D.C.: Americana Press, 1986.

- Sandler, Corey. Washington, D.C., Williamsburg, Busch Gardens, Richmond and Other Area Attractions. Lincolnwood, Ill.: Verulam, 2000.

- Schultz, Patricia. 1,000 Places to See in the United States & Canada Before You Die. New York: Workman Publishing, 2011.

- Secretary of the Interior. Report of the Secretary of the Interior for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1899. Department of the Interior. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1899.

- Select Subcommittee on Education. Aid to Fine Arts: Hearing Before the Select Subcommittee on Education of the Committee on Education and Labor, House of Representatives, Eighty-Seventh Congress, First Session, on H.R. 4172, H.R. 4174, and Related Bills to Aid the Fine Arts in the United States. Hearing Held in Washington, D.C., May 15, 1961. Select Subcommittee on Education. Committee on Education and Labor. U.S. House of Representatives. 87th Cong., 1st sess. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1961.

- Silber, Nina. Landmarks of the Civil War. New York: Oxford University Press, 2003.

- Smith, Carol. "Portraying the Black Atlantic: Americanisation and the National Museum." In Issues in Americanisation and Culture. Jude Davies, Neil Campbell, and George McKay, eds. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2004.

- Ward, David C. 2004 Charles Willson Peale: Art and Selfhood in the Early Republic Berkeley, California : University of California Press

External links

[edit]- 1968 establishments in Washington, D.C.

- 1979 controversies in the United States

- 2010 controversies in the United States

- Art museums and galleries established in 1968

- Art museums and galleries in Washington, D.C.

- Biographical museums in Washington, D.C.

- Chinatown (Washington, D.C.)

- Greek Revival architecture in Washington, D.C.

- Members of the Cultural Alliance of Greater Washington

- National galleries

- Portrait galleries

- Smithsonian Institution museums